My parents are both Caucasian, and I have an older sister who was also adopted from Korea, and a younger brother who is my parents’ biological son. We lived in a predominantly Caucasian neighborhood and attended a school where there were a total of five students of color. My sister and I were adopted at a time when there was very little awareness about transracial adoption and the importance of honoring your child’s race and culture of origin. My parents never received training on how to be transracially adoptive parents. They were given a Korean flag, a Korean cookbook, and essentially told to bring us home and love us and everything would be okay.

Considering the lack of resources my parents had, they did well with raising my sister and me to be proud of our Korean heritage. When choosing names for us, they chose to make our Korean surnames our middle names, so we would always be able to keep a part of our Korean heritage with us. My parents sent us to Korean culture camp and drove us an hour each way to provide us with that opportunity. Through the Korean culture camps, we were able to spend a week with kids who looked just like us, and learn with them about the language and different aspects of the culture. My parents bought us books in which the characters were Korean. I remember my favorite was the Korean version of Cinderella. My parents also learned how to make a couple of Korean dishes, and my mom’s bulgogi is actually one of our family’s favorite and most requested meals when we get together for special occasions. It’s something my parents have also served to guests in their home, so it’s really neat to see them share that part of our family’s culture with others, as well.

I remember being really openly proud of being Korean in grade school. When kids were bringing things like stuffed animals and toys for show-and-tell, I brought my Korean flag. I remember even wearing my hanbok to school for a project and being so proud and feeling so special to be able to share that part of me with my classmates.

On the flip side, I was teased a lot when I was in grade school. Even though there were four other Korean students at my school, I think I was the easy target because I was quiet and shy and really sensitive. My family never talked about racism, so I knew what was happening was wrong, but I didn’t know what it was. I didn’t usually tell my parents when I was teased or bullied at school. In a way, I felt like I was protecting them from it, and I also thought there was something wrong with me, and I didn’t want my parents to know. As proud as I was to be Korean, there were nights where I laid in bed crying and praying to God, asking Him to make me white and pretty like the other girls because I was tired of being different.

When I was in high school, I stopped identifying myself as Asian because I didn’t want to be known as different anymore. I attended a large high school, so it was easier for me to blend in. I remember receiving the occasional invites from the school’s multicultural club, and being so embarrassed by them. Blending in worked well for me, as I experienced very few incidents of racism and bullying in high school. At the time, it felt really good to finally feel like I fit in and feel like I belonged, even if it meant denying a part of who I was.

When I started college, I was really excited because the school I was attending was in the city and offered a diverse student population, including a fairly large Asian population. I quickly learned that because I didn’t know my language of origin and very little about my culture, I was seen as an outcast in the Asian community. I looked Asian on the outside, and I identified as Asian, but I wasn’t Asian enough to belong. It was one thing to be rejected by people who looked different from me, but it was extremely painful to experience that rejection from people within my own racial community. When I met and married my husband, who is Mexican, I unknowingly further drove a wedge between myself and the Asian community by marrying outside of my race.

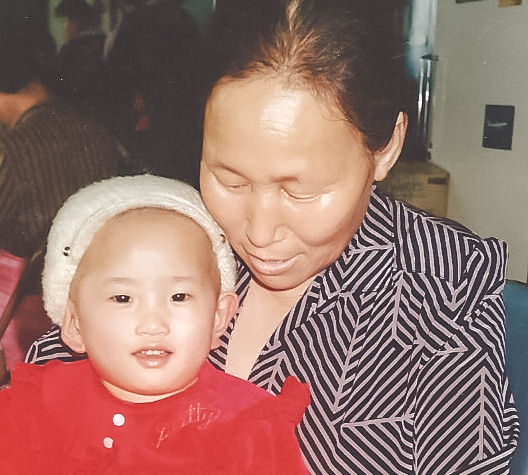

My husband and I are the parents of two biracial sons, and we have made raising them with racial and cultural pride a priority. They are well-connected with the Latino community. My husband speaks fluent Spanish, and I like to think I know enough Spanglish to get by. We don’t use Spanish as our first language in our home, but we do use Spanish phrases and terms of endearment, so our sons have been exposed to and have a basic knowledge of the language. We make authentic Mexican food at home and we celebrate Cinco de Mayo and participate in other cultural events and celebrations. We live in a diverse neighborhood and my sons attend diverse schools. I am actually really excited because my older son has an Asian teacher this year. It’s something I never had growing up, so I’m really happy that he is able to have that opportunity.

Because of the rejection I have experienced by the Asian community, we have been somewhat lax in providing our sons with opportunities to learn about their Korean culture. I do make some Korean dishes for them, and we are fortunate enough to live in an area with Korean restaurants and markets so we are able to expose them to the culture in that way. When my kids were younger, I learned about training chopsticks (http://edisonchopsticks.com.au/) through one of my Korean friends. They are available for both right-handed and left-handed children—which is great because I have one of each—and you can purchase chopsticks for the different stages of your child’s development. My boys absolutely love being able to use them at home and when we go to Asian restaurants.

It definitely takes a lot of effort to teach your children about their race. When talking with our 9-year-old, he’ll proudly say that he is Korean and Mexican. When we talk with our 6-year-old, he usually gives us his best “mad-at-the-world” face and says, “I’m not Mexican or Korean! I’m Caiden!” So, as you can see, it’s definitely a work in progress!

When you become a transracial family, your life completely changes. Be prepared that the perception of your family will change. There will be people in your life with whom you have always been close, who won’t understand it. There will be times in which you will need to examine who the people are in your life and whether or not having them around will be beneficial or detrimental to your child. I feel that transracial adoption is unique in the sense that it affords people with white privilege the opportunity to occasionally see the world through the eyes of a person of color. You may actually experience racism for the first time in your life while with your child. One important thing to keep in mind is the fact that when you are not with your child, the world will go back to seeing you as a person with white privilege. Your child, however, does not have that luxury, as the world will always see your child as a person of color.

One of my friends and former coworkers, who is a transracially-adoptive parent, wrote an article a few years ago that I absolutely love and feel every transracially adoptive parent should read. I have learned so much from her, including the concept of externalizing racism, which I feel is an incredibly important tool for your child to have. Even though it’s the PC thing to say, we don’t live in a color blind world. We live in a color aware world. While most people are accepting of different races, there are people who view the world differently and have very ignorant and close-minded beliefs when it comes to race. It’s inevitable that your child will experience racism at some point in his or her life, and it’s important for your child to be aware and know how to handle those situations. By externalizing racism, you are teaching your child that racism isn’t about them—it’s about the ignorance of others who don’t understand. This is important because the last thing you want is for your child to feel like they are less than or that there is something wrong with them because of the color of their skin.

If you haven’t experienced it already, there is a good chance that you will be approached by complete strangers who will ask questions—some of which may be completely inappropriate. I think it’s really important to trust your instincts in these situations. If you feel that something is not quite right about the person who is asking, or if the question is really inappropriate, it is absolutely your right to say something like, “Why do you ask?” without answering their question, or simply ignoring their question and removing yourself and your child from the situation. Please remember to keep in mind that your child is learning from you and the way you handle these situations.

Growing up, my family would often vacation in Arizona. On a few occasions, my parents were approached in the airport and asked if my sister and I were foreign exchange students. They were always calm in these situations and never got upset. They would just look at us, smile, and proudly say, “No, they are all ours!” It’s important to know when to engage and when not to engage in racist situations. More often than not, it’s best to just walk away and remove your child and yourself from the situation rather than engage. People who have ignorant views on race are not going to suddenly be changed or have an epiphany because you fought back or berated them for their racist behaviors. Sometimes, you just can’t fix stupid, and while it would be amazing if we could wipe all racism off the face of this planet, I think it’s unrealistic to think that a world without racism could ever be our reality.

I have heard some parents say that they don’t like answering questions about their child’s race because it’s their child’s story to tell. But, it’s important to remember that your child is learning how to tell their story from you. So, while it is important to protect your child from racist situations, it’s also important to occasionally answer the questions about your child’s race in situations—most likely with friends, family or strangers from whom you get a good and safe vibe—in which you feel it is safe to do so. I, personally, like to use these situations as opportunities to allow others to help instill racial pride in my sons. The responses we usually get in these situations involve the other person telling our sons how handsome they are, or telling us how proud we must be of our sons, etc. It is one thing to hear these things from your parent, but it’s another for your children to hear positive comments about themselves coming from complete strangers.

It is absolutely imperative that you talk to your child about race. Talk about the incidents of racism, but talk about the good experiences involving their race, as well. Don’t minimize their feelings if they tell you that someone made them feel uncomfortable or badly about the color of their skin. It’s important for your child to know that they can talk to you about the good things and the bad things and trust that you will honor their experiences. Know that your child’s racial identity will most likely change at some point in their lives. There may be times in which your child will reject the racial identity you are working so hard to develop. It’s important for you to lay the groundwork for your child, but you need to also allow your child to explore and develop their racial identity in their own way. There are so many things that are out of your child’s control when it comes to adoption. One thing they can, and should be allowed to claim ownership of, is their racial identity.

Know that nobody is expecting you to be the perfect transracially adoptive parent. I wholly believe that it takes a village to raise a child who has been transracially adopted. It’s important that you reach out to members of your child’s racial and cultural communities and give your child opportunities to learn from and be among people who look just like them. I constantly struggle with the knowledge that I won’t be the one to teach my children about the Korean culture, because as their parent, I want to be the one to teach them about who they are. As a transracially adoptive parent, it’s important to accept the things you don’t know about your child’s race and culture of origin. Rather than seeing it as a shortcoming or failure, look at it as an opportunity to learn with your child. Use every opportunity possible to involve your entire family when learning about your child’s race and culture of origin. In doing so, you are forming a stronger bond with your child and making your child feel like an important part of your family.

Know that there will be times when you will need to step out of your comfort zone to afford your child the opportunities they need to learn about their race and culture. If you don’t live in a diverse area, and you are financially able to do so, you may want to consider moving to a more diverse area. If you are unable to move, or if you have significant ties (work, family, etc.) to the community in which you currently live, it’s important to be accepting of the fact that you may need to drive an hour or two to give your child opportunities to interact with and learn from people who look like them. It’s imperative that you make every effort possible to afford your child these experiences.

I, personally, believe that it’s important to give a little in order to provide your child with these experiences. I’m not talking about giving a little in a monetary sense. Do things like take time to learn how to make an ethnic dish or a dish that is important to your child’s culture and share it with those who are helping teach your child. Take time to learn your child’s language of origin. Nobody is expecting you to become fluent in your child’s language, but a few phrases go a long way. I remember when I first met my father-in-law’s mom. I asked her if she would like something to drink in Spanish, and I seriously think she almost had a heart attack, as the last thing she expected to hear was this Asian person speaking to her in her native language! But, I remember her being really appreciative of the effort.

I personally believe that the greatest amount of scrutiny your child will experience will most likely be from members of his or her own racial and cultural communities. I can tell you firsthand that being rejected by people from your racial and cultural community is one of the most painful forms of rejection your child could ever experience. When I was told that I wasn’t “Asian enough”, it was a blow to everything I believed about myself. Your child should never have to prove that they belong or feel that they are “less than” by members of their racial and cultural community. There are many losses in adoption, but the loss of your child’s racial and cultural identity is one that can and should be avoided at all costs.

The last point I want to make is the importance of not losing yourself in the process when honoring your child’s race and culture. My dad is Italian and the Italian culture has always been very much a part of our family. My sister and I will always identify in part as Italian, and I have to say that we can make a pretty mean meatball! So, while you won’t necessarily be able to teach your child about their culture, you can and should teach your child about yours. A multicultural child will have so much more to offer the world than one with no sense of their culture at all.

Transracial parenting is not easy. There will be struggles and there will be triumphs. Do the best you can with the resources you have available to you, and never lose sight of your goal of raising your child with racial and cultural pride. Every effort you make to honor your child’s racial and cultural identity will make a difference in his or her life, and you’ll be surprised with how much you’ll learn about yourself and others along the way!

Note: This blog entry contains excerpts and elaborations from my presentation at the Crossroads of America Adoption Conference hosted by MLJ Adoptions.

Reblogged this on International Adoption Reader.

This is one of the most helpful and most well-written posts about transracial adoption that I have ever read (and I have read many). Thank you!

Blessings,

Delana

Wow, what an amazing compliment! Thanks so much, Delana!

You are most welcome. I shared it on one of my facebook pages. I can’t remember right now which one, either Nine Year Pregnancy or Adoption and Paper Pregnancy.

Blessings,

Delana

Oh, you’re Nine Year Pregnancy? Good to know! So wonderful to put a face and name to your page!

Yes, I, too, just made the connection to your facebook page. I remember commenting on something earlier today. It just took me a while to connect the dots.

I find it amazing when white parents comment that they don’t think race any longer that big of an issue. Until recently, even my husband was living in a bubble and his kids, my stepkids, are biracial. I think what it comes down to is that issues of “race” don’t effect most white people in a way that is actually felt or noticed. If you are white, living in a predominately white area, then you may likely think that race issues are no longer an issue. I think this is especially true if you live/grow up in an area where people around have the view of being “color blind” or that race should not matter. The sad fact is, in the USA, still if you are white, race doesn’t matter to you too much–white privledge. My husband grew up in a predominately white neighborhood and was taught to judge people only by their character. I grew up in a neighborhood that was mixed with black and white families and I grew up seeing racism in action and being taught that it was wrong– but that it exists. To have the idea that racism doens’t exist or that it will not effect our children is more than naive, it is dangerous. We have several children’s books that talk about differences and racism– if anyone is interested: The Skin You Live in; Whoever You Are; We’re different, we’re the same; The Skin I’m In: A First Look at Racism.

The last book I list actually addresses racism in ways that it may be experienced. Folks also may want to google “racial microaggression” as this is a big form of racism my family is addressing with my stepkids in the schools. I had not heard of this term until recently and it is really enlightening.

Well said! Thank you for sharing your insight, and thank you for the book suggestions!

Love this article! So glad I found your blog! I will be following it from now on!

I have 2 daughters. One was adopted from Vietnam, the other from China.

Thank you so much, Christy! Blessings to you and your family!

I think this is such a common experience of many adoptees who were adopted into small towns or rural areas with extremely well meaning families (such as my family) who didn’t want to make a “big deal” out of racial identity and wanted to go with the prevailing wisdom of the time of color blindness. Your description of having a Korean flag and using your Korean name as your middle name is exactly what my parents did with my brother. And he experienced the same rejection by the Asian community when he got to college. He longs to find other Asian friends, but he only really feels comfortable with people who were raised in suburban Caucasian families because he doesn’t understand the cultural nuances of Asians raised in traditional Asian families (if such a thing can be generalized). It’s kind of a cultural no-man’s land. I don’t mean to broadly lump people together for all purposes by racial categories, but I am explaining this to illustrate a point about the catch-22. I have a friend who has a similar experience in my current city who is African and is not accepted by the African American community but is also seen a categorically different than other Americans or other immigrants of European or Central American backgrounds. It is also an ethnic and racial no-man’s land in urban settings. Thank you for being willing to discuss this topic. New adoptive parents such as myself need to talk about these issues to avoid the missteps of the past.

Hi Christina,

How sweet, that you were so proud to share the Korean culture (that you were aware of), with your classmates.

You are correct… the “race” issue is important. It’s a sad fact, the words “Caucasian and American” have become incorrectly assimilated. And one can only hope, that adoptees will one day be accepted as American / European / Scandinavian etc… as anyone else who is Caucasian looking from those parts of the world and have a far more positive experience.

Really ironic that the Asian community rejected you. It is after all “Asians” who abandoned you at the beginning of your life too.

The Asians in the community who rejected you, should go to Asia. The local asian girls…. many want to marry outside their race. For example, a huge complaint by local Chinese (mainland) men, is that the foreigners are “stealing” their women!

Thanks for sharing your wisdom,

🙂

My daughter isn’t asian but I got her the training chopsticks you mentioned in this post. She’s 2 and she’s on her way to using them properly 🙂