When I started working in the adoption world, it quickly became evident that there was a division between parents who have adopted internationally, domestically, and from foster care, as well as between the agencies and organizations providing support to them. This observation was further evidenced by one of the evaluations I received from the conference I co-presented at this past summer.

I presented a session that explored loss in adoption and its effect on relationships with one of my good friends and colleagues who adopted from foster care. The adoptive parent who wrote the evaluation stated that he would have preferred to hear the material from someone who was adopted from foster care. Considering the fact that I work for an organization whose main focus is on finding forever families for children in care, it wasn’t a huge surprise to encounter someone with this mindset. This comment really stuck with me, not in a negative way, but because I have had difficulties understanding why there must be such a dramatic division between adoptive parents, regardless of where their adopted child is from. I want to explore this division by just skimming the surface and attempting to make the argument that adoptive parents aren’t as different from each other as they have come to believe.

International (or Intercountry) Adoption

Historically, international adoption has been somewhat glamorized in the sense that there has been a long-standing belief that families spend tens of thousands of dollars in an attempt to adopt “perfect” or “exotic” children from overseas. Celebrities like Angelina Jolie and Madonna have even made international adoption somewhat fashionable. There is also a belief that parents who adopt internationally have a “pie-in-the-sky” view of adoption and are naïve in thinking that their children will be perfect because of the money they spent to adopt them.

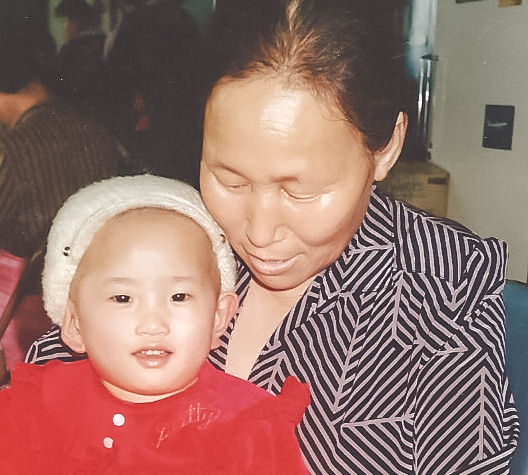

Those involved with domestic and foster care adoption sometimes harbor animosity towards those who adopt internationally because of the hundreds of thousands of kids who need forever families here in the U.S. The fact of the matter is that there are kids all over the world who need families. When I was adopted, Koreans simply did not adopt outside of their bloodline, and it was something that was frowned upon. Being that I was a girl and not a baby, my chances of finding a family domestically were slim-to-none. I spent a year in foster care prior to my adoption, and my belief is that, had I not been adopted internationally, I most likely would have aged out of care.

Most of the internationally adoptive parents I have encountered adopt from other countries because 1) they want to add to their family, and 2) because they are aware that there are children everywhere—not just in the U.S.—who need families. I have also spoken with a number of parents who choose to adopt internationally because of the overwhelming fear of the birth parents wanting their children back. While there are absolutely some very naïve internationally adoptive parents out there (as with any population of parent), a majority of my interactions have been with parents who are actually quite savvy and have a greater understanding of the issues than they are given credit for.

Most internationally adoptive parents are actually at a disadvantage due to full disclosure issues. A number of children available for adoption overseas either have little or no accompanying information (familial, medical, etc.), or the information they do have has been falsified or doctored. And some countries allow outgoing adoptions of only children with special needs.

An issue that a number of internationally adoptive parents encounter is the lack of post-adoption services. While there are many resources and support groups in the U.S. for adoptive parents, a number of them do not provide services to parents who have adopted internationally. The main reason behind the lack of services is that a number of the organizations and support groups available are funded through county, state, and federal grants that prohibit them from providing services to parents who have not adopted domestically.

I have also witnessed the “you-made-your-bed-now-lie-in-it” mentality projected towards parents who have adopted internationally. In the foster care adoption world, there can be a stigma attached to spending tens of thousands of dollars on adopting children from overseas. The belief is that if parents can spend that much on adopting a child, then they must also have the resources to fund the services to meet their child’s needs. The truth is, most internationally adoptive parents are middle class and a number of them have been able to adopt through grants and with the generous support of their friends, family, and community.

Domestic Adoption

Parents who adopt domestically through private agencies are often those seeking infants to adopt. Historically, private domestic adoption was often done in secret, as there was a great stigma attached to the inability to bear one’s own children. You will often hear of adoptees who were adopted a number of years ago and found out about it very late in life, or they always knew and were not allowed to talk about it.

Private domestic adopters are parents who are more likely than the internationally or foster care adoptive parents to experience the potential heartbreak of being matched with a child whose birth mother changes her mind and decides to keep the child. The laws vary by state, but most states allow a period of time before an adoption can be finalized (it could be a number of days or months) in which an expectant parent can revoke their consent to adopt. State laws also acknowledge the birth father, in that he is allowed to seek custody of the child even after the adoption has been finalized if, for some reason, he never knowingly consented to the termination of his parental rights.

Parents who adopt domestically through private agencies are often viewed in a similar light as parents who adopt internationally. One of the noticeable differences is that they don’t have the added stigma of not having adopted a child from the U.S.

Foster Care Adoption

Due to the nature of the organization I work for, a majority of the interactions I have are with parents who have adopted from foster care and the agencies and organizations that support them. Currently, there are over 400,000 children in foster care in the U.S., and over 100,000 are available for adoption, meaning the parental rights of their birth parents have been terminated. Many of the children and teens available for adoption have spent a considerable amount of time in foster care and have experienced multiple placements. A number of these children and teens have special needs. When a child or teen is labeled “special needs”, it doesn’t necessarily mean that they have behavioral or physical limitations. Special needs can also refer to a child who is older, a child of color, or a child who is part of a sibling group who wants to be adopted together.

Parents who adopt from foster care do so in an effort to grow their family (as with any adoptive parent) and because they see the overwhelming need to find forever families for the children and teens in the U.S. While there are some initial costs involved with adopting from foster care, they are not nearly as great as those involved with adopting internationally or through private domestic adoption. The resources and supports are more readily available in the U.S. for parents who have adopted from foster care and for their children. Parents of children with considerable behavioral, physical, and medical special needs will often receive a monthly adoption subsidy to help offset some of the costs involved with meeting their child’s needs. These adoption assistance payments are generally very minimal and, while they are helpful to those who receive them, they often cover only a small fraction of the ongoing expenses involved with meeting the needs of these children.

Why You’re Not That Different

There are many reasons why adoptive parents are not that different, but a few of the main reasons are listed below:

- Loss. At the core of all adoption is loss. Every adopted child has experienced loss, regardless of where they were adopted from. The loss of one child is not necessarily greater or more relevant simply because they were adopted from foster care as opposed to internationally. It doesn’t work that way, and it shouldn’t work that way. The same goes for adoptive parents. All parents have their unique reasons for forming their family through adoption. All adoptive parents experience the loss of not having given birth to their child—it affects some more than others—but the loss is there. There are moments of pain and moments of happiness in all forms of adoption. The journey may have started differently, but every journey has its trials and tribulations. It is important for adoptive parents to understand that, while the adoption journeys are different, similar issues are prevalent in all forms of adoption.

- Core issues in adoption. There are 7 core issues in adoption—Loss, Rejection, Guilt/Shame, Grief, Identity, Intimacy & Relationships, and Control/Gains (Silverstein, D. & Roszia, S, 1982.) Parenting a child is not easy, and parenting an adopted child can be even more difficult! Most adoptive parents will experience at least some of these core issues at some point during their adoption journey. Some of these issues can be overwhelming, and the need for support in coping with these issues is critical.

- The need for resources and support. All adoptive parents need resources and support to help them along their journey. Questions arise at various points throughout a parent’s adoption journey. All adoptive parents need support from people who have been there—from people who understand.

- Identity. Adoption changes families, and it can change the way society views your family, especially those who adopt transracially and transculturally. Your traditions will most likely change to embrace your child’s race and culture. The people with whom you associate may change. These changes have the potential to be overwhelming, and the need for support and education will be great.

The pain of one adoptive parent should not be viewed as more significant or relevant than another. Rather than focusing only on the things that set you apart from other adoptive parents, focus on the similarities that can be used in supporting each other. I have seen the power of parent-to-parent support. I have seen the difference it can make when an adoptive parent who previously felt isolated and alone realizes that there are other parents who understand and are going through similar situations. Remember to rally around each other and celebrate the differences, but celebrate the things that unify you as well. You’ll find that you will feel much less isolated, and you’ll be surprised at what you’ll learn from adoptive parents you may not have previously turned to for support!

I always look forward to your posts.

Thanks so much, Mark!

Well thought out and presented. Brava!

Thanks, Kim! 🙂

Excellent post…thank you….I live in Italy and it’s more challenging to raise a transracial son than in US and Canada where a multicultural, multiethnic community is more common…we are getting there slowly….

Thanks so much! It’s good to hear that improvements are being made in Italy. Baby steps can go a long way!

Agreed. I am actually in Guangzhou, China, right now with my new toddler daughter doing the immigration paperwork. I was adopted domestically as an infant, and two of my siblings were adopted through foster care. I have been a little surprised at how each of our experiences, different as they are, have overlapping elements and the same core experiences. I find that the personality of the individual plays a much larger part in their (and the whole family’s) experience of adoption than where the child came from.

This really is a great post. I’ve only recently found your blog, and it’s becoming one of my favorites.

That said, I’m not sure that part of your description of private domestic adoption is completely accurate.

“The laws vary by state, but most states allow a period of time before an adoption can be finalized (it could be a number of days or months) in which an expectant parent can revoke their consent to adopt.”

There is a difference between the revocation period – the period during which expectant parents can “take back” their termination of parental rights – and the time ’til finalization. My daughter’s adoption is not yet final, but her birthmother’s rights were terminated 5 days after her birth, when she signed the TPR. At that time, her birthmother’s consent was irrevocable. Similarly, when my son was born, his birthmother waited 3 days before signing TPR, and it was irrevocable the next day, when it was approved by the judge. Finalization can take anywhere from one month to several years, but once the birthparents’ rights are terminated, and the revocation period, if any, has ended, it is very difficult for a birthparent to revoke consent and regain his or her rights.

I want to say this because I’ve seen your post linked to by several different adoption groups, as well it should. It’s a great post that people should read. I’m just concerned that the common error – equating the period until finalization with the revocation period – might perpetuate the “birthparents can come back” myth that seems to drive some people away from domestic adoption.

I enjoyed reading your article. The only thing that made me post was your mentioning that adoptive families have the loss of not having biological children. Not everyone wants to have biological children. I have never wanted to have biological children so I don’t have any feelings about it.

I know it seems mean to say that when it seems that many people come to adoption through infertility, but the reality is that we’re all different.

Agreed. [by the way, I love the article, and while every adoption story is unique, we all experience similar things].

My parents and grandparents adopted because they could not conceive on their own, but my husband and I had 5 home-baked children before we adopted our youngest daughter.

We all have our own story. Same theme, different harmonies.

~Erin (2nd generation adoptee, mother of 6 including one adopted)

Great post thankkyou