As parents, we spend our kids’ entire childhood focusing on loving them, supporting them, meeting their needs, helping to shape their identities, and instilling in them the values and morals we hope they will carry with them throughout their lives. It can be difficult to wrap our minds and our hearts around the fact that our kids are growing with each passing year, and that there may come a time when they won’t need us in the same ways we have grown so accustomed to throughout the years.

Parenthood is not an easy journey by any means, and we often spend a lot of it not really knowing what the heck we are doing! We work diligently to prepare our kids for living their lives in a way that feels right and successful for them, and many of us pride ourselves in doing so. However, there is one important issue that will likely arise for our kids as they grow and mature—an issue that many parents don’t feel comfortable even thinking about in the context of their kids, much less talking about or preparing them for. If you haven’t already guessed it—yes, that issue is sex. Aaaand, yes, I am going there.

Are you ready for this? I, honestly, don’t know that I am either, but here goes.

Sex. It is a completely natural thing, right? Our bodies consist of organs and glands and other complex biological parts and processes—the makeup and mechanics of which I am not going to even pretend to know about—that all make sex possible. It can be a way for us to connect with a partner; it can be a way for some of us to grow our families; and it can help to fulfill a variety of our emotional, psychological, physical, and biological needs. So, why is it so difficult for us to talk about with our kids, and why is it important for parents to have those discussions—especially with kids who have been adopted?

Why is it so difficult to talk about?

While sex is completely natural and something that a number of us have experienced ourselves, historically, it has been something deemed inappropriate to talk openly about. For many, it is an experience that is shared with another person in the privacy of our homes and behind closed doors or other places that can help protect us from exposing our most intimate selves to the world. It is within those experiences that we can open ourselves up to being vulnerable, to connecting emotionally and physically with a partner, and allowing ourselves to feel somewhat free and uninhibited.

For those of us who have experienced it, we all have our own memories of when it first happened, with whom we shared the experience, where it happened, etc. Some of us were ready for it to happen, and some of us were not. For some, the first experience was as positive as a first time can be—for others, it was an experience we wish we could forget. Regardless of how, when, where, or with whom it happened—I think it is safe to say that most of us will agree that our first time had an effect on us and likely changed us in some way.

Many people believe they are ready for sex when it first happens, and many are subsequently surprised to discover how unprepared they actually were. While the physical aspect of a person’s first time is important and may make for some truly memorable moments, more often than not, it will be the emotional aspect of it all that they will carry with them for a long time after the fact and may have a profound impact on their future sexual experiences.

An important part of being a parent is protecting our kids from anything that may cause harm to them or to others. Regardless of whether our first experiences were positive or something we would rather forget, it can be difficult to think of our kids as being ready for something as mature and intimate and life-changing as sex. Sex can be a wonderful experience, but we are all well aware that it can also be extremely harmful—both physically and emotionally. As parents, we want to protect our kids from things like sexually transmitted diseases, early pregnancy, sexual violence and abuse, and the other potential physically harmful or consequential aftermaths of sex. And, we want and need to do our best to help protect them from the emotional and psychological implications of it as well.

As parents, it is overwhelming and a little heart-wrenching to think of our kids as ever being ready for or interested in having sex, but we would be doing ourselves and our kids a great disservice by living in denial about the fact that it will happen someday—whether we are ready for it or not.

Why it is important to talk about sex with your child who has been adopted?

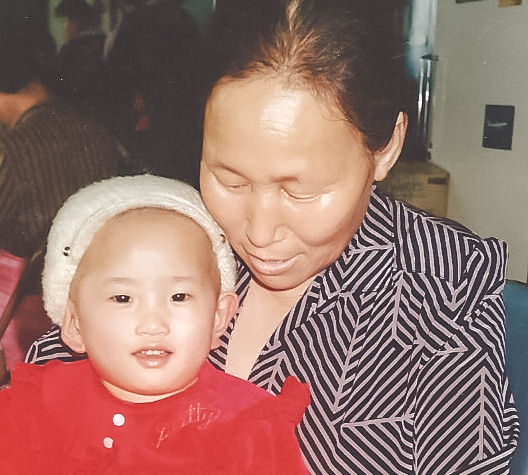

It has taken a long time and a lot of introspection for me to get to this place, but I will fully admit that before I met my husband and became a mom, my understanding of and beliefs about love were extremely distorted and convoluted. When I experienced the trauma of losing my birth mother, my brain responded to that trauma and loss by wiring itself to view the world in a different way. Whereas most infants and toddlers who maintain their connections with their birth mothers feel safe and loved and cherished, my perspective of the world was based on the belief that people who love me will always leave me. With that as the foundation upon which I approached my life and every experience and relationship within it, I subsequently formed an understanding and belief that love always comes at a cost and that I had to give something in order to receive it. I had the choice to either spend my life running from love or fighting for it, and I chose to fight for it.

In other words, I spent my life believing that love was something that I had to be in constant fear of losing.

I have spent a vast majority of my life not knowing my worth and not having the ability within myself to believe in or embrace my value in this world. Knowing that my birth mother made the decision to not keep me in her life—to not have a relationship with me at all—made it really difficult to shape my identity and form a belief about my own worth in a positive or self-loving way. In terms of my physical being, I viewed it as something to hate. As a young girl, I often wondered if my birth mother would have loved me if I had been beautiful. I grew up in the shadow of my gorgeous, tall, and popular sister—who also happened to be adopted—and I spent most of my childhood believing that the kids in school didn’t like me and teased me because I wasn’t pretty enough…because I didn’t look like them. I never learned or believed that my body was something that was worth protecting—it was simply the shell of me that existed only to contain all of the emptiness and broken pieces of who I was inside.

Having attended a private, Catholic school during my formative years, I was pretty sheltered from many realities of the world. The only extent of my sex education consisted of the abstinence-only message I received during grade school. Before high school, I knew nothing about condoms or birth control pills and I knew very little about STDs and teen pregnancy—only that they were bad and they were consequences of having sex before marriage. Attending a public high school certainly changed all of that for me in the sense that I became much more aware of the world around me, but I had also reached that period in my life where I believed myself to be invincible—as many teenagers do—and that everything that happened to other girls would never happen to me.

I started dating a guy from a different school (because I was super cool like that) during my junior year of high school. After years of feeling painfully invisible while watching my friends experience the countless and very dramatic ups and downs of their relationships, it felt amazing to finally have someone in my life who saw me as beautiful and someone worth getting to know on a different level. It was the first time in my life where I felt loved by someone who wasn’t my family, and the euphoria of it all was exciting and a little addicting in a way. We dated for several months before we reached the point of being “ready”. For me, losing my virginity to him became a way of holding onto someone I felt was slipping away. I remember very little about it beyond feeling guilty, empty, and somewhat lost after it happened.

The relationship ended, and I began my battle with severe depression and anxiety shortly thereafter. At the time, I didn’t realize how devastating it would be to experience the loss of that relationship. I didn’t realize how empty I would feel and how much I would miss feeling wanted and seen and loved by someone other than my family. After that relationship ended, I found myself craving those feelings of being needed and wanted and seen and loved. It became almost like a drug to me and I was reckless and stupid and thoughtless in my pursuit to find someone or something to fill the void the loss of that first relationship had created within me. As a result of the choices I made, I became pregnant during my senior year of high school. Due to severe stress, extreme and rapid weight loss, and a number of other factors, it eventually became medically necessary for me to terminate the pregnancy.

I never believed any of it would happen to me—but it did.

As I look back on the period of my life between high school and when I met my husband—knowing what I know now—I truly believe that a number of the choices I made were done so in pursuit of something to fill the void created by the losses I have experienced in my life. I often hear people say that having a biological connection to someone doesn’t matter—but it does. It can mean the world to someone who has never had that type of connection in their life. I love my family more than anything and my parents provided me with a really good life, but I still fantasized as a young girl about life with my birth mother—my birth family. There was a subconscious craving within me for that biological connection to someone…anyone. That need and desire for a biological connection was fulfilled when I gave birth to my oldest son. There are no words that could ever express what it felt like to hold him in my arms and to finally look into the face of someone with whom I shared a resemblance—someone who shared my DNA.

That moment of becoming a mom was profound and life-changing beyond measure. Not only did he fill a void within me—his very existence gave my life purpose and meaning. I always dreamed of becoming a mom, and I remember promising him the world in that moment of first meeting him. He provided me with an opportunity to love someone unconditionally and to feel some of that love in return.

The desire to create a family or a life you feel you never had is a common theme among children, teens, and adults who have experienced foster care or adoption. Young people who have had very little in life to call their own—along with a distorted sense of self worth—may develop a belief that their body is the only thing of value they have to give, rather than seeing it as something worth protecting. This may lead them to search for love and connection anywhere they think they might find it, which can involve potentially risky and reckless behaviors.

Tips for talking with your child or teen about sex

As a mom of tween and teen boys, I am not an expert on talking to kids about sex, nor would I ever claim to be. However, I strongly believe in talking to kids about it and starting at an early age and in age-appropriate ways. Due to some experiences in my own life and what I have learned in my work as a volunteer sexual violence crisis counselor throughout the past 11 years, it has always been important to my husband and me to talk to our kids about sex and relationships. Included on the list below are suggestions and some of the ways in which we have attempted to help prepare our sons for their future relationships:

- Starting early. We started having the “good touch, bad touch” talk with our oldest son when he was around 3 or 4. At this point, he knew the concept of right vs. wrong and had an awareness of his body to the extent that we could talk with him on a very basic level about which body parts were inappropriate for other people to see or touch, who is allowed to see those body parts, and in what context would it be appropriate for them to do so (i.e., his pediatrician while doing a check-up exam at an appointment—and only when Mama and Papa are in the room, etc.). These discussions usually occurred during bath time.

- “No” means “no”, and “stop” means “stop”. This is a message we have tried to instill in our sons in various ways throughout the years, starting from when they were very young (around 3 or 4 years old). For example, if we were having a tickling match, the moment someone said “stop”, we would be hands-off—everyone would stop, and we were done. Now that the boys are older (they are now 11 and 14), they do know what sexual violence is and they understand the importance of respecting their partner, their partner’s body, and their partner’s right to say “no” or “stop” at any time and at any point during their relationship.

- Teaching respect and acceptance. Respect for themselves and for others is something we have always worked to instill in our sons. This has included discussions of the right to say no to things like sex, peer pressure, etc., and the right to make decisions for themselves, regardless of what others may think. We talk regularly about embracing diversity and everything that makes us unique and treating all people with respect and kindness. These discussions include topics of race, gender identity, sexual orientation, religion, socioeconomic status, etc.

- Talking openly about love and relationships. Both of the boys have each had their first girlfriends (and, yes, my head did explode when that happened!), and we have used those opportunities to talk about things like what love is and what love isn’t, what it means to love and respect your partner, the ups and downs of relationships, what it means to be in love with someone, what an equal partnership should look like, etc. Because they are at an age where they can easily be embarrassed when talking about girlfriends, we try to do so in a way that is respectful, lighthearted (but not teasing), doesn’t make a big deal out of it, and doesn’t shame or embarrass them for choosing to be in a relationship. My husband and I have also made it a point to show our sons what love and a healthy relationship can look like. We share in responsibilities as a family. My husband and I are affectionate towards each other (in appropriate ways), and we don’t attempt to hide it from the boys. We screw up. We argue. We break down. We get back up. We apologize to each other and to our sons (because parents get it wrong and need to apologize, too). We support each other in our decisions and we back each other up as parents and as partners. We work through our issues together whenever possible, and we try to support each other through all of the ups and downs of life.

- Talking about sex. The boys have known about sex for a while, through friends at school and from what we have discussed with them at home. We started talking to them about sex a couple of years ago, and we tried to keep the initial discussion pretty lighthearted. (Let’s just say it may or may not have included one of us singing part of the chorus of “2 Become 1” by the Spice Girls.) It has always been important for my husband and me to not stigmatize sex or make it feel shameful to our sons or something they need to hide from us or be embarrassed about. They know it is something that is completely natural and an experience that people who are in love can choose to share with each other. We have talked about the importance of waiting until they and their partners are ready. Both of the boys have expressed interest in girls, but they are well aware of the fact that we will love and support them regardless of who they choose to love. They know about the importance of protecting themselves and their partners when they have sex. We have also discussed pregnancy and the importance of accountability and helping to raise and support their child, should they become fathers before they have found a life partner. I am sure there will be many more discussions about sex, sexual safety, and related issues, but we are thankful to have reached a point with the boys where talking about it feels fairly normal for all of us (something we have been known to do over a plate of spaghetti at dinner). As a general rule, we try to keep things pretty light in our home, because that is what works for our family. It has always been important for us to avoid fear-based, judgmental, or shaming language or tactics when talking about sex with our sons. Rather than focusing the discussions on what we feel is morally right or wrong, we attempt to keep the focus primarily on the physical and emotional safety of our sons and their future partners. Whether we like it or not, the decision of whether or not to have sex and when they feel ready to do so will ultimately be up to our sons and their future partners. It is inevitable and we have always felt that it is our job as their parents not to shame them or judge them or put the fear of God in them with regard to sex—the best thing we can do for them and for their future partners is to prepare them so that they are able to make safe, responsible, respectful, mature, loving, and informed decisions when they each choose to take that step in life.

As a parent, you know your child better than anyone, and what has worked for my family won’t necessarily work for yours. In fact, the purpose of this post was only to encourage you to talk to your kids about sex and, whenever possible, to do so in an open, honest, loving, and nonjudgmental way. I also hoped to share that talking with your kids about sex doesn’t have to be mortifying or embarrassing or cringe-inducing for you or for your kids.